Fake News Funny Yellow Journalism Hillary

| Topics in journalism |

|---|

| Professional issues |

| News • Reportage • Writing • Ideals • Objectivity • Values • Attribution • Defamation • Editorial independence • Education • Other topics |

| Fields |

| Arts • Business • Environs • Fashion • Music • Science • Sports • Trade • Video games • Weather |

| Genres |

| Advocacy journalism |

| Social impact |

| Fourth Estate |

| News media |

| Newspapers |

| Roles |

| Journalist • Reporter • Editor • Columnist • Commentator • Photographer • News presenter • Meteorologist |

| |

Imitation news, besides known as junk news or pseudo-news, is a type of yellow journalism or propaganda that consists of deliberate disinformation or hoaxes spread via traditional news media (print and broadcast) or online social media. The term Fake news is a neologism used to describe made news, stories that are not true. This blazon of news, institute in traditional news, social media, or fake news websites, has no footing in fact, but is presented equally being factually accurate. Imitation news is written and published usually with the intent to mislead in lodge to impairment an agency, entity, or person, and/or gain financially or politically, often using sensationalist, dishonest, or outright made headlines to increase readership. Digital news has brought back and increased the usage of yellow journalism. Such news is and then frequently reverberated as misinformation in social media but occasionally finds its mode to the mainstream media as well.

Contents

- 1 Definition

- 2 Identifying fake news

- 3 History

- 3.1 Ancient

- 3.2 Medieval

- 3.3 Early on modern flow

- 3.4 Nineteenth century

- three.5 Twentieth century

- four Contemporary impact

- 4.1 On the Internet

- 4.one.1 Social media

- 4.1.2 Fake news websites

- iv.1.3 Internet bots

- 4.1.4 Internet trolls

- 4.1 On the Internet

- five Response

- 6 Criticism of the term

- 7 Notes

- 8 References

- nine External links

- 10 Credits

Fake news undermines serious media coverage and makes it more difficult for journalists to cover significant news stories. Many news organizations claim proud traditions of belongings government officials and institutions accountable to the public. The proliferation of simulated news raises the issue of property the media itself answerable. As powerful influences of public opinion, purveyors of news have a responsibility to act in the interest of the betterment of human social club rather than seeking financial or other gain for themselves.

Reporters with various forms of "fake news" from an 1894 analogy by Frederick Burr Opper

Definition

Fake news is a neologism often used to refer to made news, stories that are just not true. This blazon of news, found in traditional news, social media, and on fake news websites, has no footing in fact, but is presented as being factually accurate. It is a type of yellow journalism or propaganda that consists of deliberate disinformation or hoaxes spread via traditional news media (print and broadcast) or online social media.[ane]

Imitation news can be characterized as "stories that are probably simulated, have enormous traction [pop appeal] in the culture, and are consumed by millions of people." They are "stories that are made out of sparse air. By most measures, deliberately, and past any definition, that's a lie."[two]

In some cases, what appears to be fake news may be news satire, which uses exaggeration and introduces not-factual elements that are intended to amuse or brand a bespeak, rather than to deceive. Fake news may be distinguished non just past the falsity of its content, but likewise by its intent and purpose, past the "character of [its] online circulation and reception."[3] Fake news is written and published with the intent to mislead, usually in order to impairment an bureau, entity, or person, and/or gain financially or politically,[4] [v] oftentimes using sensationalist, dishonest, or outright fabricated headlines to increase readership.

Seven types of fake news tin can be identified:[6]

- satire or parody ("no intention to cause harm merely has potential to fool")

- false connection ("when headlines, visuals or captions don't support the content")

- misleading content ("misleading employ of information to frame an issue or an individual")

- false context ("when 18-carat content is shared with false contextual information")

- impostor content ("when genuine sources are impersonated" with simulated, made-up sources)

- manipulated content ("when 18-carat information or imagery is manipulated to deceive", as with a "doctored" photo)

- fabricated content ("new content is 100% false, designed to deceive and do damage")

Identifying fake news

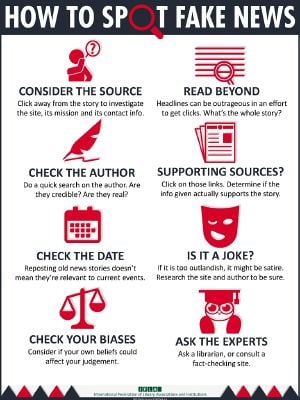

Infographic How to spot fake news published by the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions

The International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) published a diagram (pictured at right) to assistance people in recognizing fake news, with the post-obit points:[seven]

- Consider the source (to understand its mission and purpose)

- Read beyond the headline (to sympathize the whole story)

- Check the authors (to meet if they are real and apparent)

- Appraise the supporting sources (to ensure they support the claims)

- Check the appointment of publication (to see if the story is relevant and up to appointment)

- Ask if it is a joke (to decide if it is meant to be satire)

- Review your ain biases (to see if they are affecting your judgment)

- Enquire experts (to get confirmation from independent people with knowledge).

History

Imitation news, or its equivalent by whatever other name, is not a new phenomenon. History records numerous instances of false rumors and lies being spread nigh rivals and enemies. For example, colonial America, the American Revolution, and the early American presidents alike suffered numerous attacks and false portrayals in print, a trouble exacerbated by the emergence of the free printing intended to create a better informed public.[8] This problems, however, existed long before the invention of the printing press, as tin be seen in the following historical examples.

Ancient

In the thirteenth century B.C.E., Rameses the Not bad spread lies and propaganda portraying the Battle of Kadesh as a stunning victory for the Egyptians; he depicted scenes of himself smiting his foes during the boxing on the walls of nearly all his temples. The treaty between the Egyptians and the Hittites, even so, reveals that the battle was really a stalemate.[9]

During the second and third centuries C.E., simulated rumors were spread about Christians claiming that they engaged in ritual cannibalism and incest.[10] In the late third century C.E., the Christian apologist Lactantius invented and exaggerated stories about pagans engaging in acts of immorality and cruelty,[11] while the anti-Christian writer Porphyry invented similar stories virtually Christians.[12]

Medieval

Blood libels against Jews were a mutual class of anti-Semitic imitation news during the Middle Ages. These were sensationalized allegations that a person or group engaged in human sacrifice, frequently accompanied by the claim that the claret of victims, frequently children, was used in various rituals and/or acts of cannibalism.

For example, in 1475 a fake news story in Trent, Italy claimed that the Jewish community had murdered a ii-and-a-half-year-one-time Christian infant named Simonino. The story resulted in all the Jews in the city being arrested and tortured; fifteen of them were burned at the stake. Pope Sixtus Four himself attempted to postage stamp out the story; notwithstanding, past that point, it had already spread beyond control.[xiii]

Early modern menses

Afterward the invention of the printing printing in 1439, publications became widespread but in that location was no standard of journalistic ethics to follow. It took until the seventeenth century for historians to begin the practise of citing their sources in footnotes.

In the American colonies, Benjamin Franklin wrote fake news near murderous "scalping" Indians working with King George III in an endeavour to sway public opinion in favor of the American Revolution.[13]

During the era of slave-owning in the United States, supporters of slavery propagated imitation news stories about African Americans. In one instance, stories of African Americans spontaneously turning white spread through the s and struck fear into the hearts of many people.[13]

Rumors and anxieties about slave rebellions were common in Virginia from the offset of the colonial catamenia. One particular instance of fake news regarding revolts occurred in 1730. The serving governor of Virginia at the time, Governor William Gooch, reported that a slave rebellion had occurred simply was effectively put down, although this never happened. Later on Gooch discovered the falsehood, he ordered slaves plant off plantations to be made prisoner and punished.[14]

Nineteenth century

One famous instance of fake news in the nineteenth century was the Swell Moon Hoax of 1835. The New York Lord's day published articles near a real-life astronomer and a made-up colleague who, according to the hoax, had observed baroque life on the moon. The fictionalized articles successfully attracted new subscribers, and the penny paper suffered very picayune backfire afterward information technology admitted the next calendar month that the series had been a hoax.[xv] Such stories were intended to entertain readers, and not to mislead them.[xvi]

From 1800 to 1810, James Cheetham made utilize of fictional stories to advocate confronting Aaron Burr.[17] His stories were oft defamatory, and he was sued for libel.[18]

Xanthous journalism peaked in the mid-1890s during the apportionment state of war between Joseph Pulitzer's New York World and William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal. Pulitzer and other yellow journalism publishers even goaded the United States into the Spanish–American War, which was precipitated when the United states of americaSouth. Maine exploded in the harbor of Havana, Cuba.[nineteen]

Twentieth century

Fake news became popular and widespread in the early twentieth century. During the Kickoff World War, an example of anti-German atrocity propaganda was that of an declared "German Corpse Factory" in which the German battlefield dead were rendered down for fats used to make nitroglycerine, candles, lubricants, homo lather, and kick dubbing.[20] Unfounded rumors regarding such a mill circulated in the Centrolineal printing starting in 1915, and by 1917 the English-language publication North China Daily News presented these allegations as true at a time when Britain was trying to convince China to bring together the Allied war try. This was based on new, allegedly truthful stories from The Times and the Daily Mail that turned out to be forgeries. These faux allegations became known as such afterward the war, and in the Second World War Joseph Goebbels used the story in order to deny the ongoing massacre of Jews equally British propaganda. The story also "encouraged subsequently disbelief" when reports nearly the Holocaust surfaced afterwards the liberation of Auschwitz and Dachau concentration camps.[21]

Afterwards Hitler and the Nazi Party rose to power in Germany in 1933, they established the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda nether the control of Propaganda Government minister Joseph Goebbels.[22] The Nazis used both impress and circulate journalism to promote their agendas, either past obtaining ownership of those media or exerting political influence.[23] Throughout World War Two, both the Axis and the Allies employed fake news in the form of propaganda to persuade the public at home and in enemy countries.[24] The British Political Warfare Executive used radio broadcasts and distributed leaflets intended to discourage German troops.[22]

During 1932–1933, The New York Times published numerous articles by its Moscow bureau chief, Walter Duranty, who won a Pulitzer prize for his series of reports near the Soviet Union. Withal, the depiction of Russian federation every bit "a socialist paradise" was faux news fed to Duranty past Stalin. [25]

Orson Welles explaining to reporters about his radio drama "War of the Worlds" on Sunday, October xxx, 1938, the day later on the broadcast

"The State of war of the Worlds" is a 1938 episode of the American radio drama anthology series The Mercury Theatre on the Air. Directed and narrated by histrion and filmmaker Orson Welles, the episode was an adaptation of H. K. Wells' novel The War of the Worlds (1898), presented every bit a series of false news bulletins. Although preceded by a clear introduction that the testify was a drama, it became famous for allegedly causing mass panic, although the reality of the panic is disputed as the program had relatively few listeners. An investigation was run by The Federal Communications Committee to examine the mass hysteria produced by this radio programming; no law was found broken.[26] This issue was an case the early stages of society's dependency on data from the media. Simulated news can even exist found inside this example: the true extent of the "hysteria" from the radio circulate was been falsely recorded. The most farthermost instance and reaction afterward the radio broadcast was a grouping of Grover Mill locals attacking a water tower considering they falsely identified information technology as an conflicting.[27]

Contemporary bear upon

In the twenty-first century, the impact of imitation news became widespread, as well as usage of the term. Thus proliferation of fake news has been considered a class of psychological warfare and a threat to democracy.

The opening of the Internet to the public in the 1990s was meant to allow greater admission to information. Over time, however, the Net grew to unimaginable heights with information coming in not-stop from sources all over the globe. This allowed it to be a host for unwanted, untruthful, and misleading information by anyone, disseminated virtually instantly via social media.[28]

Writer Terry Pratchett, who had a groundwork as a journalist and press officer, was among the outset to be concerned about the spread of fake news on the Internet. In a 1995 interview with Nib Gates, founder of Microsoft, he suggested that anyone could brand up a treatise and put it online, without any peer review or checking of historical sources: "At that place'southward a kind of parity of esteem of data on the net. It's all there: there's no way of finding out whether this stuff has whatever bottom to it or whether someone has just made it up." Gates was optimistic and disagreed, saying that "electronics gives us a style of classifying things" and the "way that you can bank check somebody's reputation will be then much more sophisticated on the net than it is in print." However, Pratchett was correct in his prediction of how the internet would propagate and legitimize fake news.[29]

Twenty-first century fake news is often created with the intention of increasing the fiscal profits of the news outlet. For media outlets, the ability to attract viewers to their websites is necessary to generate online advertising revenue. Publishing a story with false content that attracts users benefits advertisers and improves ratings. Easy access to online advertisement revenue, increased political polarization, and the popularity of social media, primarily the Facebook news feed, take all been implicated in the spread of fake news.[1] Facebook users play a major role in feeding into imitation news stories past making sensationalized stories "trend."[thirty]

Another issue in mainstream media is the use of the filter chimera, a "bubble" that gives the viewer a specific slice of the information based on private search histories and other data. Such curated content provides customized information that may create faux or biased news because only part of the story is being shared, the portion the viewer likes.[31]

In improver to the explosion of fake news, the twenty-first century also saw an increase in popularity of satirical news, whose purpose is non to mislead but rather to inform viewers and share humorous commentary about real news and the mainstream media.[32] American examples of satire (equally opposed to simulated news) include the television show Saturday Nighttime Live'southward Weekend Update, The Daily Testify, The Colbert Report, The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, and The Onion newspaper.[33] [34]

Earlier the 2016 U.Southward. presidential election campaign involving Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, imitation news had not impacted the election procedure and subsequent events to such a loftier caste.[35] Subsequent to the 2016 election, the issue of fake news turned into a political weapon, with supporters of left-wing politics saying that supporters of right-wing politics spread false news, while the latter claimed that they were existence "censored."[35] The miracle affects both sides, with simulated news stories from the left-wing abounding virtually President George Due west. Bush, for example.[36]

Fake news has been used for political purposes in other countries. For case, during the 2019 Hong Kong anti-extradition pecker protests, the Chinese government was accused of using simulated news to spread misinformation regarding the protests. This included describing peaceful protests as "riots" with "radicals" seeking independence for the metropolis.[37]

- Use of the term past Donald Trump

President Donald Trump claimed that the mainstream American media regularly reports fake news, particularly news that portrayed him in a bad calorie-free.[38] In September 2018, National Public Radio noted that Trump had expanded his use of the terms "false" and "phony" to "an increasingly broad variety of things he doesn't like."[39]

His utilize of the term increased distrust of the American media globally, particularly in Russian federation. His claims gave credibility to stories in the Russian media that characterization American news, such as reports of atrocities committed past the Syrian authorities against its own people, as nothing more than than fake American news.[xl]

On the Cyberspace

When the Internet was kickoff made accessible for public use in the 1990s, its primary purpose was for the seeking and accessing of information. Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the World Broad Web, imagined it as "an open platform that would allow everyone, everywhere to share information, admission opportunities and collaborate across geographic and cultural boundaries." Still, in 2017, he noted three significant trends that must be resolved if the Net is to exist capable of truly "serving humanity": fake news, and the surge in the apply of the Internet by governments for both citizen-surveillance purposes and for cyber-warfare purposes.[41]

In the mid 1990s, Nicholas Negroponte anticipated a globe where news through technology get progressively personalized. In his 1996 volumeExistence Digital he predicted a digital life where news consumption becomes an extremely personalized experience and newspapers adapted content to reader preferences. He forecast that the interactive world, the amusement world, and the data world would eventually merge. A digital optimist, he believed that computers and the internet would make life meliorate for anybody.[42]

Negroponte'southward prediction has indeed been reflected in news and social media feeds of mod mean solar day. Withal, the ubiquity of internet news and the presence of social media platforms makes information technology easier for false information to diffuse apace, with the result that fake news has the tendency to get viral. False news has been found to spread online "farther, faster, deeper, and more than broadly than the truth in all categories of information."[43] Also, it has been shown that it is people not the technology that are responsible for disseminating false news and information. The tendency for people to spread false information has to practise with human behavior. People are attracted to events and information that are surprising and new, which cause high-arousal in the encephalon.[44] This leads people to retweet or share fake data. On Twitter, false tweets take a much higher hazard of being retweeted than truthful tweets. The centre-catching titles that are common in such posts discourage people from stopping to verify the information. As a result, online communities form effectually a piece of false news without any prior fact checking or verification of the veracity of the information.

In the twenty-first century, the capacity to mislead was enhanced by the widespread use of social media. More one-half of Americans access news through social media more than than traditional newspapers and magazines.[45] With the popularity of social media, fake news is omnipresent among the viewer population with the result that it spreads hands beyond the internet.

Many people use their Facebook news feed to become news, despite Facebook not existence considered a news site. This, in combination with increased political polarization and filter bubbles, has led to a trend for readers to mainly read headlines.[46]

Simulated news websites

False news is ofttimes spread through the use of simulated news websites, which, in order to gain credibility often impersonate well-known news sources.[47] [48]

These simulated news websites (also referred to equally hoax news websites) deliberately publish fake news—hoaxes, propaganda, and disinformation purporting to exist real news—often using social media to bulldoze spider web traffic and dilate their effect. Unlike news satire, faux news websites deliberately seek to be perceived as legitimate and taken at face value, oft for fiscal or political gain.[47]

Such sites have promoted political falsehoods in numerous countries around the world, including Frg, French republic, Myanmar, Italia, China, Brazil, Commonwealth of australia, and Bharat.[49]

Internet bots

Net bots increment the spread of imitation news, as they utilise algorithms to decide which articles and information specific users like, without taking into business relationship the actuality of the manufactures or the credibility of the sources. They tin be programmed to automatically "like" or "retweet" posts, making them appear popular. Bots also mass-produce articles, and are capable of creating imitation accounts and personalities on the web that then gaining followers, recognition, and authorization. [50]

Net trolls

In Net slang, a troll is a person who sows discord on the Internet by starting arguments or upsetting people, past posting inflammatory, extraneous, or off-topic messages in an online community (such every bit a newsgroup, forum, chat room, or blog) with the intent of provoking readers into an emotional response or off-topic discussion, often for the troll's amusement. Whereas it in one case denoted provocation, the term came to be used to signify the abuse and misuse of the Net. Cyberspace trolls feed on attention. When interacting with each other, trolls ofttimes share misleading information that contributes to the fake news circulated on social media sites. [51]

Trolling is closely linked to fake news, every bit cyberspace trolls are perpetrators of faux information, information that tin often be passed forth unwittingly by reporters and the public alike.[52]

Response

The spread of fake news and its impact on politics worldwide[49] has led to a number of attempts to curtail this phenomenon, past individual countries impacted by faux news besides by as organizations that fight misinformation.

In an endeavor to reduce the effects of fake news, fact-checking websites such as Snopes and FactCheck have posted guides to spotting and avoiding false news websites.[47] [53]

The International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN) supports international collaborative efforts in fact-checking, provides preparation, and has published a fact-checking lawmaking of principles for "organizations that regularly publish nonpartisan reports on the accuracy of statements by public figures, major institutions, and other widely circulated claims of interest to society."[54]

Social media sites and search engines, such as Facebook and Google, received criticism for facilitating the spread of fake news. Both of these corporations take taken measures to explicitly prevent the spread of fake news; critics, nevertheless, believe more activity is needed.[55] Google subsequently launched Google News Initiative (GNI) to fight the spread of fake news. It has 3 goals: "to elevate and strengthen quality journalism, evolve business models to bulldoze sustainable growth and empower news organizations through technological innovation."[56]

Efforts have been made by a number of governments to address the problem of fake news. However, without a clear definition of what imitation news is, or is not, there is the danger that laws against fake news are just as likely to make it possible for governments to "control uncomfortable stories" every bit to prevent the spread of untrue ones.[57] A somewhat different arroyo was taken in Taiwan, where a new curriculum designed to teach critical reading of propaganda and the evaluation of sources was introduced into schools. Called "media literacy," the course gives chidren training in journalism in the new information society.[58]

Following are the responses past several governments to the result.

- United Kingdom

Alex Younger, Principal of the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) in the Great britain, called fake news and propaganda damaging to democracy: "The risks at stake are profound and represent a key threat to our sovereignty; they should be a concern to all those who share democratic values."[59] In January 2017, the UK Firm of Commons commenced a parliamentary inquiry into fake news. Damian Collins, the committee chairman, said the ascension of propaganda and fabrications is "a threat to commonwealth and undermines conviction in the media in full general."[threescore]

- Commonwealth of australia

The Australian Parliament also initiated an investigation into "fake news." The inquiry looked at several major areas in Commonwealth of australia to find audiences well-nigh vulnerable to fake news, by considering the impact on traditional journalism, and by evaluating the liability of online advertisers and past regulating the spreading the hoaxes. [61]

- Prc

China has used the spread of fake news every bit a reason to increment cyber governance and increasing internet censorship. Ren Xianling of the Cyberspace Assistants of People's republic of china recommended using identification systems so that a "reward and punish" organization could be implemented to avoid fake news.[62]

- Malaysia

In April 2018, Malaysia implemented the Anti-Fake News Beak 2018, a controversial law that accounted publishing and circulating misleading data as a crime punishable by up to six years in prison house and/or fines of upwards to 500,000 ringit.[63] In developing its new law, the Malaysian government divers fake news as "news, information, information and reports which is or are wholly or partly false," which applies beyond all forms of media, and to producers and sharers both in and out of the land. The law also makes it illegal to share fake news stories. The vagueness of this law means that satirists, stance writers, and journalists who make errors may face prosecution.[57]

Criticism of the term

Although the term "fake news" has not been around long, it has been used in and then many contexts that its significant has already been lost.[38] As a result, some chose to replace the term with alternatives.

By Baronial 2017 Facebook had stopped using the term "fake news" and used "faux news" in its place.[64]

In November 2017, Claire Wardle, co-founder of the nonprofit organization Outset Typhoon which is focused on addressing mis- and disinformation, publicly rejected the phrase "imitation news," finding it "woefully inadequate." She replaced information technology with "information pollution" and distinguished between three types of bug:

- Mis-information: false information disseminated without harmful intent.

- Dis-information: created and shared by people with harmful intent.

- Mal-information: the sharing of "18-carat" information with the intent to cause impairment, such as some types of leaks, harassment, and hate speech online.[65]

In October 2018, the British authorities decided that the term "fake news" would no longer be used in official documents because it is "a poorly-defined and misleading term that conflates a multifariousness of simulated information, from 18-carat error through to foreign interference in democratic processes." This followed a recommendation past the Business firm of Commons' Digital, Civilisation, Media and Sport Committee to avoid the term and to use "misinformation" or "disinformation" instead.[66]

Neither the words 'fake' nor 'news' effectively capture this polluted information ecosystem. Much of the content used as examples in debates on this topic are not false, they are genuine but used out of context or manipulated. Similarly, to understand the unabridged ecosystem of polluted information, we need to consider far more than than content that mimics 'news.'[67]

Notes

- ↑ one.0 1.1 Zeynep Tufekci, It'due south the (Commonwealth-Poisoning) Gold Age of Free Speech communication Wired, Jan 16, 2018. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ↑ What'southward "fake news"? lx Minutes producers investigate CBS News, March 26, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ↑ Liliana Bounegru, Jonathan Grayness, Tommaso Venturini, and Michele Mauri, A Field Guide to "Fake News" and Other Information Disorders Public Data Lab, January 8, 2018. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ↑ Elle Hunt, What is faux news? How to spot it and what you can do to finish it The Guardian, December 17, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ↑ Robert Schlesinger, Fake News in Reality U.S. News & Earth Written report, Apr xiv, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2020

- ↑ Claire Wardle, Fake news. It's complicated First Draft, February sixteen, 2017. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ↑ How to Spot Fake News IFLA, January 27, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ↑ Jackie Mansky, The Age-One-time Problem of "Simulated News" Smithsonian Magazine, May vii, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ↑ William Weir, History's Greatest Lies: The Startling Truth Behind World Events Our History Books Got Wrong (Crestline Books, 2018, ISBN 978-0785836568).

- ↑ Everett Ferguson, Backgrounds of Early on Christianity (Eerdmans, 2003, ISBN 978-0802822215).

- ↑ David M. Gwynn, Christianity in the Afterward Roman Empire: A Sourcebook (Bloomsbury Academic, 2015, ISBN 978-1441106261).

- ↑ Gillian Clark, Christianity and Roman Society (Cambridge University Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0521633864).

- ↑ 13.0 thirteen.1 13.2 Jacob Soll, The Long and Brutal History of Fake News Politico Magazine, December eighteen, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ↑ Mary Miley Theobald, Slave Conspiracies in Colonial Virginia Colonial Williamsburg Periodical, Wintertime 2005-2006. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ↑ "The Great Moon Hoax" is published in the "New York Sun" This Day in History, August 25, 1835. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ↑ Brooke Borel, Fact-Checking Won't Save Us From Fake News FiveThirtyEight, Jan four, 2017. Retrieved Jan 21, 2020.

- ↑ James Cheetham, 9 letters on the subject of Aaron Burr's political defection (University of California Libraries, 1803).

- ↑ Aaron Burr 5. James Cheetham Statement re Ballot of 1800, 18 August 1805 Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ↑ Milestones: 1866–1898 Office of the Historian. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ↑ Stephen Badsey, The German Corpse Manufacturing plant: A Written report in First Globe State of war Propaganda (Helion and Company, 2019, ISBN 978-1911628279).

- ↑ David Clarke, The corpse factory and the birth of fake news BBC News, Feb 17, 2017. Retrieved Jan 21, 2020.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 The Man Behind Hitler: World War Ii Propaganda PBS. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ↑ The Press in the 3rd Reich Holocaust Encyclopedia. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ↑ Becky Little, Within America'due south Shocking WWII Propaganda Car National Geographic, Dec 19, 2016. Retrieved Jan 21, 2020.

- ↑ Judy Dempsey, Judy Asks: Can Faux News Be Browbeaten? Carnegie Europe, January 25, 2017. Retrieved Jan 21, 2020.

- ↑ Orson Welles's "War of the Worlds" radio play is circulate This Day in History. Retrieved Jan 21, 2020.

- ↑ Martin Chilton, The War of the Worlds panic was a myth The Telegraph, May vi, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ↑ Eugene Kiely and Lori Robertson, How to Spot Simulated News FactCheck.org, Nov 18, 2016. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- ↑ Alison Inundation, Terry Pratchett predicted rise of fake news in 1995, says biographer The Guardian, May 30, 2019. Retrieved Jan 25, 2020.

- ↑ Dave Davies, Simulated News Expert on How False Stories Spread And Why People Believe Them NPR, December 14, 2016. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ↑ Jon Martindale, Forget Facebook and Google, burst your own filter chimera Digital Trends, December 6, 2016. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ↑ A look at "Daily Prove" host Jon Stewart's legacy CBS News, August half dozen, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ↑ Ryan Bort, Why SNL's 'Weekend Update' Change Is Brilliant Esquire, September 12, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ↑ Area Human Realizes He'southward Been Reading Fake News For 25 Years NPR, August 29, 2013. Retrieved Jan 27, 2020.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Sabrina Tavernise, As False News Spreads Lies, More Readers Shrug at the Truth The New York Times, December 7, 2016. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ↑ Amelia Tait, Fake news is a problem for the left, too New Statesman, February 11, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ↑ Lily Kuo Beijing'southward new weapon to muffle Hong Kong protests: fake news The Observer, August eleven, 2019. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ↑ 38.0 38.ane Henri Gendrea, The Internet Made 'Fake News' a Thing—Then Fabricated Information technology Nothing Wired, February 25, 2017. Retrieved Jan 25, 2020.

- ↑ Tamara Keith, President Trump's Description of What'due south 'False' Is Expanding NPR, September 2, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- ↑ Jim Rutenberg, A Lesson in Moscow Well-nigh Trump-Mode 'Culling Truth' The New York Times, Apr 16, 2017. Retrieved Jan 25, 2020.

- ↑ Jon Swartz, The Earth Wide Web's inventor warns information technology'south in peril on 28th anniversary United states Today, March 11, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ↑ Nicholas Negroponte, Existence Digital (Vintage, 1996, ISBN 978-0679762904).

- ↑ Soroush Vosoughi, Deb Roy, and Sinan Aral, The Spread of Truthful and False News Online MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy, 2018. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ↑ Jonah Berger and Katherine Fifty. Milkman, What Makes online Content Viral? Journal of Marketing Research, 2011. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ↑ Jeffrey Gottfried and Elisa Shearer, News Employ Across Social Media Platforms 2016 Pew Research Center, May 26, 2016. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ↑ Olivia Solon, Facebook's failure: did fake news and polarized politics get Trump elected? The Guardian, November 10, 2016. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ↑ 47.0 47.one 47.ii Kim LaCapria, Snopes' Field Guide to Fake News Sites and Hoax Purveyors Snopes, January xiv, 2016. January 29, 2020.

- ↑ Ben Gilbert, Fed up with faux news, Facebook users are solving the trouble with a simple listing Business concern Insider, November fifteen, 2016. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Kate Connolly, Angelique Chrisafis, Poppy McPherson, Stephanie Kirchgaessner, Benjamin Haas, Dominic Phillips, Elle Hunt, and Michael Safi, Fake news: an insidious trend that'due south fast becoming a global problem The Guardian, Dec 2, 2016. Retrieved Jan 29, 2020.

- ↑ Joanna M. Burkhardt, Tin Engineering science Save U.s.? Affiliate three of "Combatting Fake News in the Digital Historic period" Library Technology Reports 53(viii)(2017). Retrieved Jan 29, 2020.

- ↑ Joel Stein, How Trolls Are Ruining the Internet Time, August 18, 2016. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ↑ Terry Gross and Charlie Warzel, The Twitter Paradox: How A Platform Designed For Gratis Speech Enables Internet Trolls NPR, October 26, 2016. Retrieved Jan 29, 2020.

- ↑ Eugene Kiely and Lori Robertson, How To Spot Fake News FactCheck.org, November 18, 2016. Retrieved January xxx, 2020.

- ↑ Lawmaking of Principles International Fact-Checking Network. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ↑ Daisuke Wakabayashi and Mike Isaac, In Race Against Fake News, Google and Facebook Stroll to the Starting Line The New York Times, January 25, 2017. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ↑ Mallory Locklear, Google puts $300 1000000 towards fighting false news Engadget, March twenty, 2018. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Richard Priday, Fake news laws are threatening free oral communication on a global scale Wired, April 5, 2018. Retrieved Feb 3, 2020.

- ↑ Nicola Smith, Schoolkids in Taiwan Will At present Be Taught How to Identify Fake News Time, April 17, 2017. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ↑ Jim Waterson, MI6 Chief Says Fake News And Online Propaganda Are A Threat To Democracy BuzzFeed, December eight, 2016. Retrieved Feb 3, 2020.

- ↑ Fake news research past MPs examines threat to democracy BBC News, Jan 30, 2017. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ↑ Amy Remeikis, Parliament to launch inquiry into 'fake news' in Commonwealth of australia The Sydney Morning Herald, March thirty, 2017. Retrieved Feb 3, 2020.

- ↑ Catherine Cadell, Red china says terrorism, fake news impel greater global internet curbs Reuters, Nov 19, 2016. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ↑ Hannah Beech, Malaysia Moves to Ban 'False News,' Worries About Who Decides the Truth The New York Times, April 2, 2018. Retrieved February three, 2020.

- ↑ Will Oremus, Facebook Has Stopped Saying "False News" Slate, August 8, 2017. Retrieved Feb three, 2020.

- ↑ Francesca Giuliani-Hoffman, 'F*** News' should be replaced by these words, Claire Wardle says CNN, November 3, 2017. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ↑ Margi Potato, Authorities bans phrase 'fake news' The Telegraph, Oct 23, 2018. Retrieved Feb 3, 2020.

- ↑ Alex Hern, MPs warned against term 'fake news' for get-go live commission hearing outside U.k. The Guardian, Feb 7, 2018. Retrieved February iii, 2020.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Amarasingam, Amarnath. The Stewart / Colbert Effect: Essays on the Real Impacts of Fake News. McFarland & Company, 2011. ISBN 978-0786458868

- Badsey, Stephen. The German Corpse Manufacturing plant: A Study in Start World War Propaganda. Helion and Visitor, 2019. ISBN 978-1911628279

- Cheetham, James. 9 letters on the subject of Aaron Burr's political defection. Academy of California Libraries, 1803.

- Clark, Gillian. Christianity and Roman Lodge. Cambridge Academy Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0521633864

- Dice, Mark. The Truthful Story of Imitation News: How Mainstream Media Manipulates Millions. The Resistance Manifesto, 2017. ISBN 978-1943591022

- Ferguson, Everett. Backgrounds of Early Christianity. Eerdmans, 2003. ISBN 978-0802822215

- Gwynn, David M. Christianity in the Later Roman Empire: A Sourcebook. Bloomsbury Academic, 2015. ISBN 978-1441106261

- Negroponte, Nicholas. Existence Digital. Vintage, 1996. ISBN 978-0679762904

- Weir, William. History's Greatest Lies: The Startling Truth Backside World Events Our History Books Got Wrong. Crestline Books, 2018. ISBN 978-0785836568

- Young, Kevin. Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Braggadocio, Plagiarists, Phonies, Postal service-Facts, and Fake News. Graywolf Press, 2017. ISBN 978-1555977917

External links

All links retrieved February four, 2020.

- NOT Existent NEWS: A look at what didn't happen this week The Associated Press

- NYPR On The Media

- Inside a Fake News Sausage Factory: 'This Is All About Income' The New York Times November 25, 2016

- To Fix False News, Await To Yellowish Journalism

- Fake News Owen Spencer-Thomas.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia commodity in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Artistic Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due nether the terms of this license that can reference both the New Earth Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this commodity click here for a list of adequate citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers hither:

- Fake_news history

- Fake_news_website history

The history of this commodity since information technology was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of "Imitation news"

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Fake_news

Post a Comment for "Fake News Funny Yellow Journalism Hillary"